True honesty makes us vulnerable. Most of us spend our whole lives pretending to be the things that we should be. We hide the worst parts of ourselves, hoping that the pretense will somehow overcome the deep-seated secret desires and maladies that lie just out of sight. Most of us won’t tell the truth even when it is directly asked of us: How does this make you feel? Are you okay? What’s wrong?

I can’t pretend that I am better than giving the most perfunctory answer: “Good,” or even less specific, “Fine.” What a pasty, spineless answer to such momentous questions.

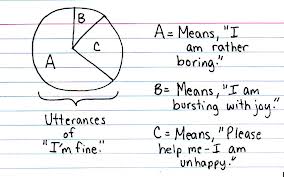

The word “fine” means satisfactory or acceptable, with a slightly negative connotation. I think, for the most part, it is an outright lie. If I tell you I’m fine, I am not being truly honest. I’m telling you what I think you want to hear and what I am willing to say. It is an unspoken pact: You don’t really want to know about me and I don’t really want to tell you.

Why is it ingrained into us to lie about or hide how we are really feeling? We are programmed, by whom, I do not know, to answer that things in our lives are “fine.” As children, we learn that our parents want us to be “fine”, and so we only tell them the things that will make them think that we are normal, semi-positive human beings. Often, we are really hiding the truth in the ultimate form of emotional or physical self-preservation.

If I told you the truth, you would realize how “not fine” I am, and I can’t deal with that right now.

One day, shortly after we moved to Portland, Abigail was helping me pick up the house. I asked her to put a pair of tweezers away in the back bathroom. When she came out into the living room again, her face was pale and her eyes were wide. I asked if she was okay, and she said, “Yes.” When I probed her more, she said she had seen something in the back bedroom. Being me, I was suddenly sure that she had seen the ghost of a previous tenant or an axe murderer staring at her from outside her window.

It could happen. We do live in apartments.

I asked her questions like, “How tall was he? Did it look like a man?” and Abigail refused to respond. I assumed it was just her imagination, and so I said, “Well, let’s go back and see if it’s still there, okay?” At this, she began to shake violently, still not saying a word. I freaked out, thinking she was going into some epileptic seizure. I consoled her until she calmed down again. To prove that she was safe, I took her into the back bedroom to show her that there was nothing to be afraid of.

“There’s nothing back here…” I started, looking around the room. That’s when I saw the burn mark on the electrical socket.

As soon as my eyes lit on the charred socket, the burnt tweezers a few feet away, Abigail began screaming. It was the most horrible scream I have ever heard, the sound of someone being tortured within an inch of their life. I dropped to a knee, looking into Abigail’s eyes. “Oh my gosh, oh my gosh…Are you okay? Are you okay?” She was frozen with fear, screaming, her eyes glazed and unmoving. I tried to look into her mouth, to check her tongue for burns, her fillings for melted metal. She had been eating a purple popsicle, so her mouth was all discolored. My panic increased, as I wasn’t sure if electrocution would cause that kind of reaction.

I grabbed her and ran to the phone, literally forgetting which number to call in case of emergency. I ran to the neighbors, banging on the door and hoping that they had a local phone line. It took me a second, but I remembered that I could call 911 on my cell phone.

I was far from “fine.”

I took Abigail out in front of the apartment, to get her away from whatever she had seen when she put the tweezers into the light socket. I sat with her, soothing her screams, explaining gently that she was “Going to be okay,” all the while holding my own scared tears in my throat.

By the time the EMTs arrived, Abigail had stopped crying almost completely. Her vitals were normal, although she was in a little bit of shock. She answered their questions like a pro, and hugged the teddy bear they brought out of the house for her. By the time they were about to leave, Abigail had a fireman sticker, and I had a copy of emergency transport refusal paperwork. Kyle came home. From the sheer number of police cars, emergency vehicles and EMTs, he was sure that we were both dead. He was relieved to find that Abigail was eagerly eating an ice cream that the neighbor had given her. By the time the crew left, she was laughing easy.

Over the next few days, I got the story out of her. She had wanted to see what would happen if she put the tweezers into the socket. When she had gotten close, the safety fuse had blown, arcing blue sparks across the room. She had left the room and come to see me. When I asked her if she was okay, she didn’t know how to tell me the truth. There were no words to describe how she felt, so her gut instinct was to tell me that she was “fine.” She was also afraid that I would be mad if I found out. “Fine” was the best way to keep her secret.

Maybe its not dishonesty that makes us tell the world that we are okay, even when we are freaking out on the inside. Maybe we just don’t have the words to define exactly how we are doing. I think we use it to mask the reality of our situation, usually in a sense of self-preservation that is old and deep. If we are “fine,” we are just like everyone else, right? There is no fear of being pushed out of the pack if we are positive, contributing, stable members of the community.

I have come to the conclusion that it is okay to be “not fine.” It is okay to be angry, frustrated or bored. Even though most people don’t want a real answer to that question, I think it is important to know what the real answer is. More importantly, I think it is vital that we start answering the question honestly.

A good friend of mine talked with me recently. She has had a hard life, keeping her family together when it was very difficult, starting her motherhood at a very young age. Over the past few months, she has been having emotional breakdowns that she can’t quite control. She is embarrassed by her excessive crying, yelling and sadness. She says to me, “I just want to be normal again. I just want to be fine.”

What I say to her, I say to you: There is no such thing as “normal.” “Fine” is a lie that we tell people so that we can hide the things we are too afraid to say.

Perhaps there is a world where people segment their existence into categories like “satisfactory” and “unsatisfactory”. In that world, “fine” and “normal” might exist.

I think the world is bigger than that.

In my world, I have good days, I have honest days, I have angry days and I have rebellious days. I have days that make me thank God that I exist, and I have days that make me wish I had never been born.

Living a truly honest life means accepting who we are and how we feel every moment, and being willing to be vulnerable in that moment. It means taking the time to reflect and answer the important questions, even if the asker doesn’t want to hear the answers. Life is not about simply existing acceptably, but existing dynamically. In order to do that, we must begin to answer those little questions with courage, knowing that the answer will probably never be easy.

You Have Time for Just One More:

[su_carousel source=”category: 20″ link=”post”][su_carousel source=”category: 13″ link=”attachment”][/su_carousel]

One response to “The Ballad of the Tweezers: The Dangers of Being Fine”

I am feeling very fine! How ’bout you?